We know different kind of changes. How they work. Which levels of humanity they affect.

We all know the three ways to influence others or change behavior: pressure, bribery, or inspiration. We know this since being kids.

Pressure: “brush your teeth otherwise xyz happens”. Xyz will be never something pleasurable. It will be pain by creating directly some sort of pain or by withdrawal of something we like.

Bribery: “brush your teeth and you get the chocolate”. It will often work and we will get the action, but we may loose the big picture. And it will condition the people to get something. Always. And always more.

If the people don’t like change, it’s just a symptom of mistrust.

They don’t believe we act in their best interest.

And they don’t believe – most of the time rightful – we understand their job.

The reasons for resentments concerning change are misused power, destroying trust, and arrogance. And the arrogance is a property of the broken system. It’s the effect of a misunderstanding.

Inspiration and persuasion: “you see this new amazing StarWars teeth-brushing robot, just stick it in your mouth and it will do the rest”.

We hear often the saying “the only humans that want change is a baby in wet diapers”. This is not true.

People want change and sometimes even crave change. But people need to understand what will happen and people must belief from the heart that it is in their interest.

No one fears change when they trust and understand its benefits. In a safe environment, we’re even willing to accept changes that benefit the system, even if they don’t directly benefit us. This aligns perfectly with the vision of an intelligent organization.

However, in systems lacking trust—which is absence of safe spaces—, pressure and bribery often become the primary tools for influencing others. While these methods might deliver short-term success, they are costly and unsustainable in the long run. Constant monitoring and increasing pressure or incentives are required for every action—control in its most expensive form. It may work, but it comes with significant costs.

No one enjoys working in such environments, leading to high staff turnover, health issues, and internal politics. It’s common to find large, successful organizations where only 20-30% of the effort is actually directed toward serving the customer.

The rest is wasted internally, as people focus on protecting themselves in various ways. This inefficiency is costly and threatens the system’s survival—hardly the hallmark of an intelligent organization.

The need for change comes from the difference between reality and perception. The power of change comes from the crises.

The core model we use is based on Virginia Satir’s work, represented by the orange line. We’ve added a teal line to represent “reality,” whatever that may be. The point of crisis occurs when we notice the mismatch between these two lines. Interestingly, what we perceive and feel is most of the time different from what the outside world sees and perceives.

The biggest problem humans have, is that we don’t perceive reality, but create it. We think our perception is true, even if it was filtered through many layers.

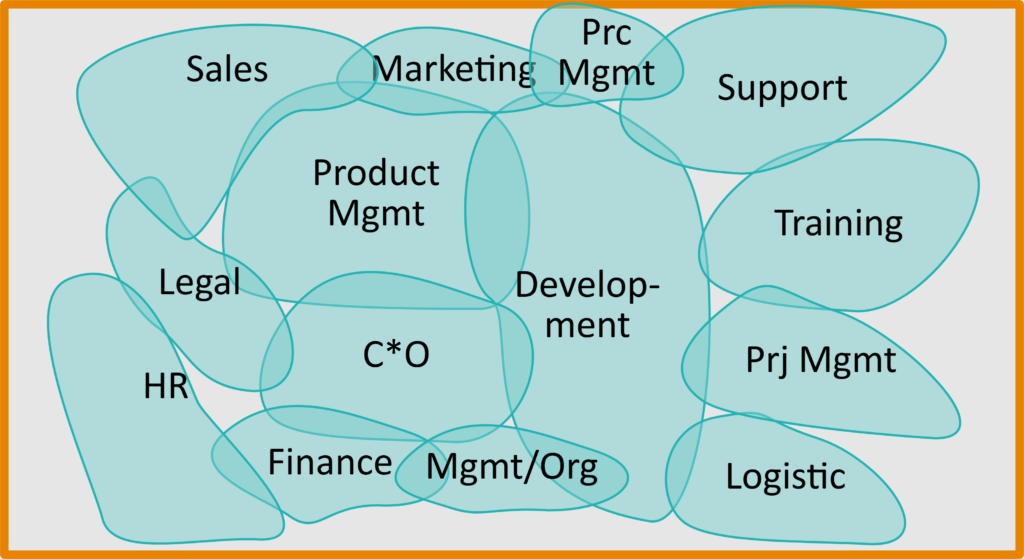

One tool to adapt continuously to changing “reality” is to use as many perspectives inside the system as possible. In the Clockwork we have the assumption that the top sees all. But relying on system theory and psychology this is not true, and just a natural bias. Everyone of us has just a personal perspective. And using the Clockwork model we can think about milieus. And none of them is right or wrong, it just has a different perspective and contribution to our shared purpose. Therefore, we need to see, hear, and understand all of us.

OrgIQ is about applying principles of healthy growth. We respect and valuate the way humans are build. The neuronal, social, and psychological structure.

Natural change is a form of growth. I don’t force plants to grow. I even can’t do it, if I want.

Humans are a bit more complicated. We can fake everything, when we are forced. But then we loose the connection between us.

Following our true selves, we can even “manage” the deepest transformations. And the cost is lower then ever before.

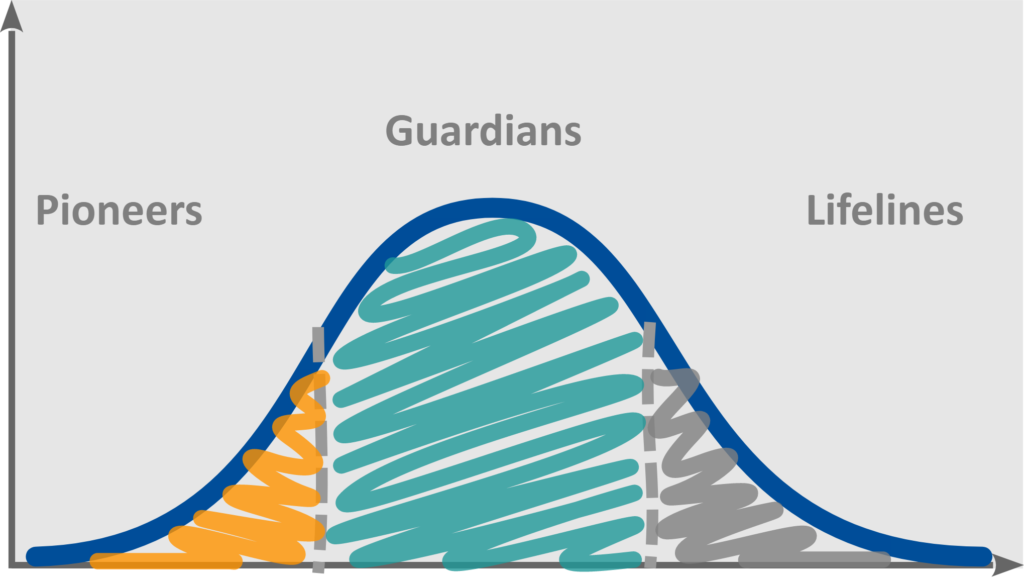

How does we react on change? The simple answer is: “different”. Depending on our role in the social system, we will drive the change (pioneers), we will evaluate the change (guardians), or we will resist the change (lifelines).

In the Clockwork Model, we often treat every group unfairly, but the pioneers and lifelines are particularly “always wrong.” Perhaps the most significant shift we need is in how we view their roles within the system—how we understand the logic and survival mechanisms that keep the system alive.

We must recognize that every group is essential. We can never predict which group will be most critical on any given day.

On a daily basis, the guardians seem most necessary. They are the core of the Clockwork. In a perfectly stable world with no change or threats, the guardians would handle everything, and that would be enough. But life is rarely that safe or predictable. Nature has equipped every system with tools to survive during challenging times.

Pioneers drive change. They seek new opportunities for growth and adaptation, challenging the system’s perception of reality. They are risk-takers, willing to sacrifice themselves to find new paths.

This is where the guardians come in. They serve as the first line of safety, evaluating the pioneers’ actions to determine if they are safe and beneficial. Over time, the guardians will either adopt these changes or reject them.

But even the guardians can fail. They may adapt to a change, only for something unexpected to happen, rendering the pioneers’ and guardians’ efforts ineffective. In the past, this could mean the end for all.

That’s where the lifelines come into play. In rare but crucial moments, they act as the backup, ensuring the population’s survival. It may take a few generations to restore balance between all roles, but the lifelines are vital.

For the system to remain stable and aligned, these three groups must engage in conscious, active dialogue and truly listen to one another.

It’s useful, when we understand, which of our actions address which level. We have here a simplified model, which should be useful enough. When we apply pressure or manipulation (bribery), we will reach only the surface (the teal part).

We loose the people, but get a (fake) respond and change. They just put on a show to avoid conflict and maintain appearances. On the surface, it looks like progress, but underneath, nothing shifts. This often leads to resignation and covert resistance, with subtle acts of sabotage creeping in. Outward compliance masks deeper discontent, slowly undermining any real progress.

Inspiration, grounded in trust, taps into our emotional core (the orange base). It’s what drives true human change.

For too long, we’ve settled for fake responses—mere echoes of fear patterns like fight, flight, freeze, or fawn.

For more on change see also our WhitePaper.